De diverse klimaat-alarmistische advertenties die Google op milieuzaken.org plaatst zijn bepaaldelijk niet die van de redactie van deze website !

feiten, getallen en opinies

Groepsdenken / Group Think

U bent hier: inhoudsopgave

-

wetenschap - klimaatpsychologie - groepsdenken

Afkorting of begrip onbekend ? Raadpleeg ons milieuwoordenboek !

De term Groepsdenken (Engels: Group-think) wordt in het algemeen spraakgebruik vaak ten onrechte aangewend voor het afwijzen van het gedachtengoed van een groep mensen waar men het helemaal niet mee eens is. Op die manier gebruikt is het woord eigenlijk niet meer dan een ordinaire discussietruc: men plakt een onvriendelijk "label" aan een persoon of diens uitspraak zonder inhoudelijk op een betoog in te gaan. Andersom hoor je dan wel eens een volgende discussietruc: "Ieder weldenkend mens zal het met me eens zijn dat...", waarbij ook al geen inhoudelijke argumentatie meer nodig zou zijn.

De algemene theoretische en practische principes van het verschijnsel Groepsdenken (een vorm van massapsychose) worden op Wikipedia gedetailleerd uitgelegd.

In een artikel op Climatgate.nl van 19-9-2019 (Frans Timmermans en het monster Trotteldrom), legt Jeroen Hetzler uit dat het Europese klimaatdenken (klimaatgekte), sinds eind 2019 onder leiding van Eurocommissaris Frans Timmermans, een duidelijk voorbeeld is van fataal uitpakkend groepsdenken.

Maarten Toonder wijdde hier al in 1964 een prachtige strip aan: Tom Poes en het monster Ttrotteldrom.

Het eiland Trottel wordt geteisterd door een alles vernietigend monster Trotteldrom.

Professor Prlwytzkofsky stelt een psychologisch onderzoek in.

Op zijn vraag “Wat is goed en wat is slecht?” krijgt hij als antwoord: “Goed is wat de meerderheid denkt, slecht is wat de minderheid denkt”

Hij wordt vervolgens zelf als ‘slecht’ de stad uitgejaagd.

Maar het verhaal loopt goed af en de Trotten leren wat de fatale effecten van groepsdenken in hun land teweeg brachten.

Door een waterhoos wordt het monster geraakt. Het uiteenvallende monster Trotteldrom blijkt geheel uit een grote drom Trotten te bestaan.

Tom Poes bekijkt de ontwikkelingen boven op een rots. De verslagen Trotten zitten met de vraag: “De meerderheid heeft ontdekt dat wijzelf het monster zijn. Wij zijn een voorgeraakt volk, eendrachtig en eensgezind. Hoe komen we zo gek?” Tom Poes antwoordt de Trotten dat zoiets komt door de eendracht. “Een menigte wordt altijd een monster dat ervan houdt dingen kapot te maken en zo.”

In het verlengde van het bovenstaande ligt Christopher Booker's rapport: Global Warming: a case study in Group Think: How science can shed new light on the most important "non-debate" of our time, Global Warming Policy report no. 28, 2018. Zie hier voor een korte recentie van dit verhelderende, maar ook schokkende rapport.

(klik op de foto voor een vergroting)

De term "Group-think" schijnt oorspronkelijk "gemunt" te zijn door William Whyte Jr. in 1952.

Maar Irving Janis liet in 1972 in zijn boek "Victims of groupthink" (in latere edities afgekort tot "Groupthink") zien dat er een wetenschappelijke structuur bestaat voor de regels volgens welke "groepsdenken" verloopt (zie ook wikipedia). Hij muntte de term opnieuw en welbewust met verwijzing naar de term "doublethink" in George Orwell's boek "1984". Ik citeer verder ui Booker's voornoemde rapport, p. 3:

In fact the only reason why his book is not much better known is that he does not himself seem to have been aware of how much more generally relevant his insights were than to just the subject of his original study. The subtitle of his book was A Psychological Study of Foreign Policy Decisions and Fiascos, and the examples he used to illustrate his thesis were all notorious failures of US foreign policy between the 1940s and the 1960s. These included the failure of America to heed intelligence warnings of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbour in 1941, General McArthur’s fateful decision to advance into North Korea in 1950, President Kennedy’s backing for the CIA’s disatrous Bay of Pigs invasion of Cuba in 1961, and President Johnson’s decision in 1965 to escalate the war in Vietnam. In a later edition he added President Nixon’s involvement in the Watergate affair.

But what Janis more generally showed through each of his carefully researched case studies was how this form of collective human psychology operates according to certain clearly identifiable rules. Janis several times set out lists of the ‘symptoms of groupthink’, and his lengthy study included much analysis of its other attributes. But for our present purpose, we can draw out from his work three characteristics of groupthink that are absolutely basic and relevant to our theme. I carefully use here the phrase ‘draw out from’ because Janis himself nowhere explicitly states that these are the three basic rules of groupthink. But they are implicit in his analysis throughout the book, and form the core of his theory as to how groupthink operates.

The three rules of groupthink

Rule one is that a group of people come to share a common view or belief that in some way is not properly based on reality. They may believe they have all sorts of evidence that confirms that their opinion is right, but their belief cannot ultimately be tested in a way that confirms this beyond doubt. In essence, therefore, it is no more than a shared belief.

Rule two is that, precisely because their shared view cannot be subjected to external proof, they then feel the need to reinforce its authority by elevating it into a ‘consensus’, a word Janis himself emphasised.

To those who subscribe to the ‘consensus’, the common belief seems intellectually and morally so self-evident that all right-thinking people must agree with it.

The one thing they cannot afford to allow is that anyone, either within their group or outside it, should question or challenge it. Once established, the essence of the belief system must be defended at all costs.

|

Rule three, in some ways the most revealing of all, is a consequence of that insistence that everyone must support the ‘consensus’. The views of anyone who fails to share it become wholly unacceptable. There cannot be any possibility of dialogue

|

|

Janis showed how consistently and fatally these rules operated in each of his examples. Those caught up in the groupthink rigorously excluded anyone putting forward evidence that raised doubts about their ‘consensus’ view. So convinced were they of the rightness of their cause that anyone failing to agree with it was aggressively shut out from the discussion. And in each case, because they refused to consider any evidence that suggested that their twodimensional ‘consensus’ was not based on a proper appraisal of reality, it eventually led to disaster.

The collective refusal to heed intelligence warnings allowed the Japanese to attack Pearl Harbour with impunity. McArthur’s hubristic decision to advance into North Korea predictably brought China into the war, with deadly results. The reckless acceptance by Kennedy and his little circle of intimate advisers of a crackpot CIA plan to invade Cuba led inevitably to an embarrassing fiasco. The massive stepping up of US forces in Vietnam produced a response that was to suck the US into ten years of frustration and a growing nightmare, which only ended with their humiliating withdrawal in 1975.

But Janis then followed this litany of failure with two examples of US foreign policy initiatives that provided a complete contrast: the Marshall Plan in the late 1940s and the ending of the Cuban missile crisis, which had threatened a new world war in 1962. He showed how the difference had been that these initiatives were driven by the very opposite of groupthink. In each case, those responsible had deliberately canvassed the widest range of expert opinion, to ensure that all relevant evidence was brought to the table. They wanted to explore every possible consequence of what was being proposed. And in each case the policy was outstandingly successful.

Once we recognise how these three elements make up the archetypal rules that define the operations of groupthink, we see just how very much more generally they have applied, in different guises, all down the ages.

An obvious example comes in the shape of most forms of organised religion. Religions are, by definition, ‘belief systems’, which, once established, have tended to become very markedly intolerant of anyone who does not share them. These outsiders are therefore condemned as ‘heretics’, ‘infidels’, and ‘unbelievers’. To protect the right- thinking orthodoxy, they must be marginalised, excluded from mainstream society, persecuted, even put to death.

Another obvious instance has been those totalitarian political ideologies, such as communism or Nazism, that likewise showed ruthless intolerance towards ‘subversives’, ‘dissidents’ or anyone not following ‘the party line’ (in the Soviet Union it was termed ‘correct thinking’). Again, such people had to be excluded from established society, imprisoned or physically ‘eliminated’.

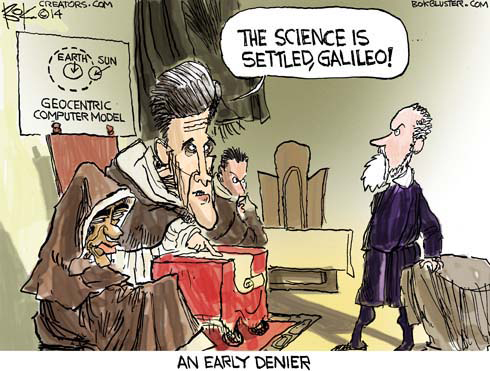

Once we recognise this pattern, we can easily identify countless other examples, large and small, throughout history; from the treatment accorded to Galileo for questioning the Church’s ‘consensus’ that the sun moved round the earth to the hysteria whipped up in the USA in the early1950s by McCarthy and the Senate Un-American Activities Committee, against anyone who could be demonised as a ‘communist’ and therefore a traitor.

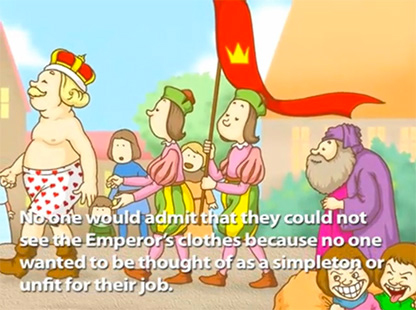

A perfect fictional depiction of groupthink in action is Hans Christian Andersen’s story The Emperor’s New Clothes. When the emperor parades through the streets in what he has been talked into imagining is a dazzling new suit, all his deferential subjects acclaim it as handsome beyond compare. Only the little boy points out that the emperor is not wearing any clothes at all, and is stark naked. And, of course, those caught up in the ‘consensus’ all viciously turn on him for pointing out the truth. |

|

De drie regels volgens welke groepsdenken verlopen worden ideaal-typisch geïllustreerd in het interview met wetenschapper Bart Verheggen in Trouw van 29-6-2019 (kijk hier indien de link is verbroken). Verheggen is is de initiator en drijvende kracht achter de webblog Klimaatverandering. De kop van het artikel begint hoopvol: "Scheidsrechter in het klimaatdebat". De 2e kop doet die hoop al snel te niet: "Het klimaatdebat is losgebarsten. Prachtig, zegt wetenschapper Bart Verheggen. Maar hij signaleert wel misleidende uitspraken in de politiek, media en op internet. Tegen die "klimaatonzin" trekt hij ten strijde.

Deze uitspraak valt binnen regel 2 van groepsdenken: dissidente meningen worden aangemerkt als "klimaatonzin", want in strijd met de consensus. Immers, zoals Janis stelt:

|

"Those caught up in the groupthink rigorously excluded anyone putting forward evidence that raised doubts about their ‘consensus’ view. So convinced were they of the rightness of their cause that anyone failing to agree with it was aggressively shut out from the discussion." |

|

‘Als je merkt dat je tegenstander gelijk heeft en jij ongelijk hebt, moet je persoonlijk, beledigend en grof worden.’ (Schopenhauer)

“Ik zie dat massamedia soms pseudosceptische argumenten tegenover de wetenschappelijke feiten over opwarming van de aarde zetten.” Een klimaatscepticus gaat dan bijvoorbeeld in debat met een wetenschapper. Media trappen daarbij in een valkuil, zegt Verheggen: het journalistieke basisprincipe van hoor en wederhoor. “Een uitstekend principe natuurlijk, maar niet als het wetenschap betreft.”

Zoals regel 2 van Groepsdenken al zegt; The one thing they cannot afford to allow is that anyone, either within their group or outside it, should question or challenge it.

Verheggen: "Een klimaatscepticus vragen om een reactie op het betoog van een klimaatwetenschapper geeft het publiek een vervormd beeld. “Zelfs als je slechts af en toe een pseudoscepticus een podium biedt, geeft dat een verkeerd signaal aan mensen die daarvoor ontvankelijk zijn.” Door experts en twijfelaars tegenover elkaar te zetten kan de gemiddeld matig geiïnformeerde kijker of lezer gaan denken: de waarheid zal wel in het midden liggen,".

Zoals regel 3 van groepsdenken al stelt: "The views of anyone who fails to share it become wholly unacceptable. There cannot be any possibility of dialogue". Het "wegzetten" van andersdenkenden als "pseudosceptici' (wat toch wel een negatieve connotatie heeft) valt ook onder regel 3: zie de latere uitwerking van regel 3, het op allerlei manieren demoniseren van andersdenkenden. Verheggen haalt in het interview ook collega Paul van Soest aan, die andersdenkenden over het klimaat "de twijfelbrigade" noemt, ook al een term met een negatieve connotatie.

Verheggen: “Maar bij het klimaat weet de wetenschap, op hoofdlijn in elk geval, heel goed hoe het zit. Verheggen heeft daar de kortst mogelijke samenvatting voor paraat. “De aarde warmt op, het komt door ons, de gevolgen zijn serieus, maar we kunnen er nog iets tegen doen.” "Elke vorm van klimaatberichtgeving die deze “robuuste conclusies” niet voorop stelt, doet volgens Verheggen geen recht aan de klimaatwetenschap", zo vervolgt het artikel. |

|

|

| De kop van het artikel in Trouw luidt "Scheidsrechter in het klimaatdebat". Een passender kop zou wellicht zijn: "Inquisiteur im het klimaatdebat" | ||

Booker vervolgt zijn uitleg over Group Think met nog 2 principes:

Regel 4: The power of second-hand thinking (na-denken en na-praten)

Janis was only really concerned with how groupthink affected small groups of people in charge of US policy at the highest level. But when we come to consider the story of the belief in man-made global warming, we are of course looking at how this was shared by countless other people: academics, politicians, the media, teachers, business executives, indeed public opinion in general.

But all these people only got carried along by the belief that manmade global warming was real and dangerous because they had been told it was so by others.

They accepted as true what they had heard, read or just seen on television without questioning it. And this meant that they didn’t really know why they thought why they did. They hadn’t thought it necessary to give such a complicated and technical subject any fundamental study. They simply echoed what had been passed on to them from somewhere else, usually in the form of a few familiar arguments or articles of belief that were, like approved mantras, endlessly repeated. Of course, we all accept a huge proportion of what we believe or think we know without bothering to check the reliability of whatever source we first learned it from, such as the idea that the Earth is 93 million miles from the Sun, or that Tokyo is the capital of Japan. We just take on trust that such things are true because everyone else does so, and assume that, if necessary, they can be confirmed by hard evidence. |

Regel 5: The power of Authrity and Prestige (de kracht van autoriteit en prestige)

But when it came to the belief in man-made global warming, another factor was at work, one which always becomes relevant when we are looking at any case of group-think. Because this was a wholly new idea, its acceptance rested on how much authority could be attributed to those putting it forward, and this was to become a crucial part of the story.

Long before Janis came up with his theory of groupthink, similar ideas had been explored in less scientific form by the French writer Gustave Le Bon, who in 1895 published a book called The Crowd. And one of his shrewdest observations was the crucial part played in changing the opinions of huge numbers of people by ‘prestige’: the particular deference paid to those who are taking the lead in putting them forward.

Niet voor niets schakelen reclame-uitingen tegenwoordig graag beroemde flimsterren en sportlieden in om het publiek tot aankopen te verleiden. Tegenwoordig noemen we ze "influencers".

This was never more evident than in the way the belief in manmade global warming came to win such widespread acceptance. The most obvious example was the unique prestige accorded to the body known as the UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). The prestige of the IPCC lay in the fact that it was presented to the world as the ultimate objective authority on the state of the earth’s climate, representing the views of all the world’s ‘top climate scientists’. If other scientists, poiticions, journalists or anyone else wished to make a point about global warming, they only had to cite the IPCC as their authority. Its pronouncements were to be treated as gospel. And even these people borrowed a little of the IPCC’s authority by the very fact that they were quoting it.

But how did the IPCC come to be given such unparalleled authority in the first place? This becomes highly relevant when we look at how closely the rise of the belief in global warming and all that followed from it was shaped by Janis’s three basic rules.

In zijn volgende hoofdstukken geeft Booker het onthutsende relaas van het ontstaan van het geloof-systeem m.b.t. catastrofale door mensen veroorzaakte opwarming van de aarde (CAGW = catasrophic antropogenic global warming), later wat afgezwakt tot climate Change (Klimaatverandering). Een verhaal van ongehoorde wetenschapsmanipulatie en bedrog, geleid door een beperkte groep mensen binnen de Verenigde Naties en diverse uitvoerende VN-instanties zoals het IPCC. Wetenschap, overduidelijk en aanwijsbaar misbruikt voor politieke doeleinden. Propaganda-machines gebaseerd op autoriteit en prestige van de Verenigde Naties. En het buitensluiten van iedereen die het met de consensus m.b.t. dit klimaat-geloof openlijk oneens durft te zijn. Zie b.v. hoe het IPCC het peer review systeem misbruikt.

In Nederland is Thierry Baudet ongeveer de enige politicus die wetenschappelijk welbeslagen in de 2e kamer strijdt tegen het vigerende klimaat-geloof en het finnanciëel-economisch desastreuse klimaatbeleid....

Regel 3 van group think wordt hierop door een demonstrante toegepast: An obvious example comes in the shape of most forms of organised religion. Religions are, by definition, ‘belief systems’, which, once established, have tended to become very markedly intolerant of anyone who does not share them. These outsiders are therefore condemned as ‘heretics’, ‘infidels’, and ‘unbelievers’. To protect the right- thinking orthodoxy, they must be marginalised, excluded from mainstream society, persecuted, even put to death.

Klik op de foto om de video te starten.

Anti-Beaudet demonstratie in Amsterdam, 2019; De mevrouw op de foto is inmiddels veroordeeld tot een taakstraf van 180 uur, waarvan 60 voorwaardelijk........

Regel 3 van het groepsdenken over klimaat kent inderdaad vele ernstige uitingsvormen:

De echte milieufascisten willen de zgn. "Global Warming Deniers" graag veroordelen voor oorlogsmisdaden. Lees: Thomas Lifson, punishing climate change deniers, American Thinker, April 13th 2015.

Ook de doodstraf wordt tegenwoordig door diverse prominente personen gepropageerd voor zgn. "klimaat-ontkenners". Zie: Gerrit van Lingen, Het groene boekje, Climategate.nl, 16-2-2019.

En als ls het aan Greenpeace ligt worden onze kinderen zo opgevoed in "de leer":

niet meer als rationeel denkende en democratisch gezinde burgers, maar als milieufascisten voor wie er nog slechts gelovigen en ongelovigen zijn: zie de video voor het lot van de laatsten, het liefst niet met een volle maag.

Bovenstaande aspecten van Groepsdenken zijn om wanhopig van te worden. Deze website milieuzaken.org geeft daarom naast vele feiten, getallen en opinies ook veel illustraties en cartoons. Dit indachtig de waarschuwing van de schrijver Oscar Wilde: "If you want to tell people the truth you have to make them laugh or they will kill you"

Verdere literatuur over group Think:

- Booker, Christopher, Global Warming: a case study in Group Think:

How science can shed new light on the most important "non-debate" of our time, Global Warming Policy report no. 28, 2018.

- Delingpole, James, RIP Chritopher Booker, The world's greatest climate change sceptic, Breitbart.com, July 3rd 2019. (kijk hier indien de link is verbroken)

- thegwpf.com, 21-02-2018, Christopher Booker: Group Think on climate change ignores inconvenient facts.

- Labohm, Hans, In memoriam Christopher Booker, Climategate, 5-7-2019.

- Labohm, Hans, Trump versus groepsdenken, Climategate.nl, 22-1-2020.

- le Pair, Kees, Klimaat en "cancel culture" - opponenten luisteren niet naar elkaar, Climategate.nl, 13-11-2022

- Pielke, Roger Jr., How Groupthink, Misinformation, And Lack Of Self-Correction Undermined Climate Science, ClimateChangeDispatch, 18-10-2023

- Wolters, Theo, “Groepsdenken” beheerst het klimaatdebat, Climategate.nl, 15-1-2012

Lees ook onze webpagina over Censuur, Cancel-cultuur en "Feiten-controleurs".

Lees hier meer over 'klimaat-psychologie"

Deze website is een activiteit van dr. Hugo H. van der Molen, Copyright 2007 e.v.

Mail ons uw commentaar, aanvullingenen en correcties !

De diverse klimaat-alarmistische advertenties die Google op milieuzaken.org plaatst zijn bepaaldelijk niet die van de redactie van deze website !